August 15th, 2021 – 2025

Siberia Before the Russian Occupation

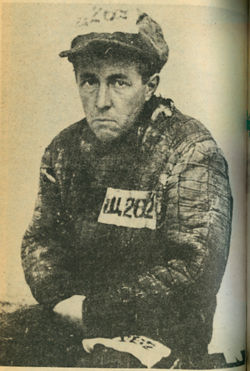

Half a million people migrated to the Russian Far East. Siberia, rich in natural resources, saw large-scale exploitation throughout the 20th century. Industrial towns sprouted across the region, and during Soviet times, the infamous penal labor system was restructured under the GULAG state agency.

Official Soviet estimates suggest that over 14 million people passed through the Gulag from 1929 to 1953, with an additional 7 to 8 million deported or exiled to remote Soviet territories, including entire nationalities. Between 1941 and 1943, 516,841 prisoners died in camps due to food shortages during World War II, though mortality rates were generally lower at other times. The size and severity of the Gulag system remain subjects of debate. For instance, Australian historian Stephen Wheatcroft argues that these camps were neither as large nor as deadly as often portrayed. Many were located in remote parts of northeastern Siberia.

After the Soviet Union’s collapse, little changed for the people of Siberia, who remained largely disconnected from the tumultuous events in Moscow. The 2008 global financial crisis, which wiped out $12 trillion of wealth, left Russia struggling to meet the demands of its military and population. Once flush with revenues from its vast energy reserves, Russia was now in dire need of new economic growth sectors. The Putin government turned its focus to Siberia’s untapped wealth of minerals and raw materials. A massive stimulus package aimed to industrialize the Siberian Oblast and link it more closely to Moscow, through initiatives like the M57 expansion in FY2018, designed to connect northern Siberian cities with the west.

The Rise of the Sons of Khanate

Siberia has long been a focus of FSB interest, and by 2019, the agency’s 24th Siberian Directorate detected internet chatter suggesting a credible threat. A group calling itself the Sons of Khanate (SOK), supposedly hardcore supporters of Potanin, emerged with the goal of launching an insurgency against the Russian government. The NSA intercepted communications from the FSB to the Russian Governor’s office, listing Siberian leaders suspected of harboring insurgents.

Though the Putin government preferred conservative responses to unrest, the situation in Siberia grew increasingly volatile. Weakened by military and economic struggles, Russia could ill afford a new conflict while its modernization efforts lagged. Relations with Europe, already frozen following the Ukraine conflict, had only just begun to thaw, leaving Russia isolated from the markets and finance necessary for its vast infrastructure and military projects.

Despite Moscow’s attempts to assert control, Siberia had lived in practical autonomy for decades. The GRU’s efforts to infiltrate local governments and social circles failed—ethnic Siberians, physically distinct from Slavic Russians, stood out in local communities. Siberian culture, more closely related to Afghan, Persian, and Chinese traditions, had developed in isolation. Siberians who had moved abroad showed little interest in returning, much less in collaborating with the Russian government to spy on their countrymen.

As GRU operations struggled, Moscow resorted to relying on a network of corrupt “thieves in law” organizations—criminal groups that had evolved from the exile communities sent to Siberian labor camps during Soviet purges. While these efforts were well-known to US and European intelligence, the GRU’s failure to recruit ethnic Siberians as informants remained largely hidden.

Siberia’s Strategic Importance

Siberia, a vast landmass with a small population, posed a major challenge to Russia’s dominance. The region’s new independence disrupted the balance of power, particularly with China, which had long protested Russian claims to the Far East. Despite Siberia’s geographic isolation from the western Russian heartland, Moscow insisted that the region remain part of the Russian Federation.

The UN was divided, with the US, France, and the UK supporting Russia, while China sought to annex nearly a million square miles of eastern Russian territory. Weak and weary from repeated wars, Russia had lost large portions of its lands. Its military, regrouping along the southern border, was far from the Siberian theater.

The Russian government issued stark warnings to China: any incursion into Russian territory would be met with full force, including nuclear weapons. Moscow vowed to use tactical nuclear weapons against Chinese forces, though it would limit strikes to the battlefield, avoiding Chinese cities or military bases. But in January 2021, when 12,000 PLA troops and 250 tanks entered eastern Russia, bypassing Vladivostok and seizing the Shaknua Peninsula, the conflict escalated.

Russia’s limited use of nuclear weapons targeted small military garrisons in the remote mountains of central Siberia. It marked the first use of nuclear arms in combat in nearly a century. US and UK satellites tracked every moment, receiving updates directly from Russian ground sensors.

The Path to World War III

In response to Russia’s nuclear strike, the PLA sank a Russian aircraft carrier off the coast of China and attacked four major Russian military bases in eastern territory. The US ambassador to China urgently pleaded with the Chinese Premier to refrain from using nuclear weapons. Though China positioned its own arsenal for use, the nuclear exchange halted.

The US, now threatening to launch ICBMs against both Russia and China, managed to de-escalate the situation temporarily, preventing all-out nuclear war. However, this conflict is widely considered the opening phase of World War III. Within a few years, major wars would erupt across South America, Africa, the Middle East, and throughout Asia and the Pacific..

Siberia Background

Siberia has long been a land of diverse nomadic groups, including the Yenets, the Nenets, the Huns, the Iranian Scythians, and the Turkic Uyghurs. One notable figure was the Khan of Sibir, who, in 630 AD, endorsed Kubrat as Khagan in Avaria. The Mongols conquered much of the region in the early 13th century, and with the breakup of the Golden Horde, the autonomous Siberian Khanate was established in the late 14th century. During the 13th to 15th centuries, the Yakuts migrated north from the Lake Baikal area under pressure from the expanding Mongol Empire.

By the 16th century, the rising power of Russia began to undermine the Siberian Khanate. Russian traders and Cossacks were the first to venture into the region, soon followed by the Russian army, which built forts farther east. Towns like Mangazeya, Tara, Yeniseysk, and Tobolsk sprang up, with Tobolsk declared the capital of Siberia. At this time, “Sibir” referred both to a fortress near Tobolsk and the surrounding territory, as noted on Gerardus Mercator’s 1595 map.

By the mid-17th century, Russia had extended its control to the Pacific, though Siberia remained sparsely populated and largely unexplored. By 1709, the Russian population in Siberia was just 230,000. Over the centuries, only a few explorers and traders ventured into the region, with Siberia primarily known for its remoteness and harsh conditions.

A significant influx of people to Siberia came in the form of prisoners exiled from western Russia and territories like Poland, especially under the katorga system. By the 19th century, around 1.2 million prisoners had been sent to Siberia. Major industrial cities like Norilsk and Magadan were originally built by prisoners and run by ex-prisoners. The construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway between 1891 and 1916 brought Siberia closer to the industrializing Russia of Nicholas II. Between 1801 and 1914, an estimated 7 million settlers moved to Siberia, most in the 25 years before World War I.

Post-World War II

After World War II, Siberia remained a critical yet underdeveloped region. Prison camps like Sevvostlag along the Kolyma River and Norillag near Norilsk housed tens of thousands of prisoners, with 69,000 in Norillag alone by 1952. Northern Siberia’s major industrial cities were originally established by forced labor during the Soviet era. However, even into the 1970s, vast stretches of Siberia, including nearly 70 million miles of forest and tundra, remained unexplored. Although surveys of its rich mineral deposits were conducted, little was done to exploit them as the Soviet Union became increasingly bogged down by its invasion of Afghanistan, which marked the beginning of the regime’s decline.

Post-Soviet Era

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian government embarked on ambitious plans to modernize and connect eastern and western Russia. These plans included not just road construction, but the installation of fiber-optic cables, cell towers, and internet networks to link the vast and isolated regions of Siberia to the rest of the country. However, the Russian government, reliant on outdated state corporations, struggled with a lack of technical expertise and equipment.

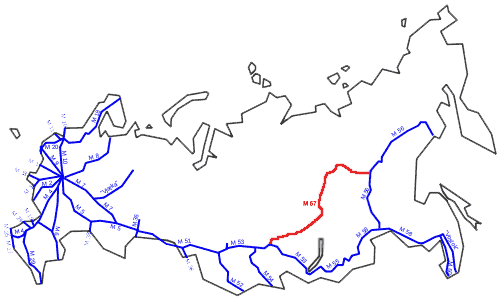

One key project was the M57 highway, part of Putin’s efforts to connect northern Siberia to Moscow. Despite protests from regional Siberian officials who wanted local construction firms to lead the project, the Russian government selected the oil construction company Stroytransgaz. Within two years, the project was in disarray: nearly 10 billion rubles had been spent, but only 150 miles of road had been built, leaving much of Siberia disconnected from the existing highway network.

Corruption and mismanagement plagued the project. A report found that 20% of the funds were stolen, while another 30% was laundered through shell corporations linked to state officials and Russian mobsters. As frustration grew, Putin’s government had no choice but to bring in foreign companies for help. US and UK engineering firms eventually directed the project to a Canadian company experienced in building roads through dense, remote woodlands. By 2014, progress had been made, but tensions were rising between Moscow and Siberian officials, who resented the growing influence of the central government.

Growing Siberian Nationalism

The initial incidents of vandalism at M57 construction sites—such as the destruction or theft of equipment—were dismissed as isolated acts. However, the GRU and FSB were slow to recognize the growing nationalist sentiment among Siberians. Inter-agency rivalry between the FSB and GRU meant that intelligence on the region was sparse. By 2016, the Siberian Directorate had only 250 personnel, and the region’s semi-autonomous nature had left it largely free from the Kremlin’s direct influence.

The lack of federal presence in eastern Siberia extended to law enforcement as well. The GRU, FSB, and Russian Federal Police had a minimal presence and relied on local sheriffs for cooperation. Human intelligence sources were scarce, and the federal agencies had little insight into the growing nationalist movement or the grievances of the Siberian population.

Siberia’s vast distance from Moscow and its history of isolation had fostered a sense of independence. Ethnic Siberians, culturally distinct from Slavic Russians, felt disconnected from the central government. These sentiments, coupled with the Russian government’s struggles to complete infrastructure projects and its reliance on foreign companies, further fueled Siberian nationalism and set the stage for a growing conflict between the region and the Kremlin.

Escalation to Open Conflict: The Birth of the Siberian Republic

The Siberian separatist movement, which started as an intellectual rebellion against Russian colonialism in the 19th and early 20th centuries, found new life in the internet age. As young Siberians rediscovered their forgotten cultural identity, they became more aware of the potential for self-rule, independent from the central Russian government. What began as a cultural revival soon turned into organized political dissent, with Siberian nationalists using the decentralized internet infrastructure to bypass Moscow’s control. This digital autonomy allowed the movement to spread like wildfire, especially among younger generations who had grown disillusioned with the Kremlin’s grip on their homeland.

Despite Moscow’s attempts to stifle the rising nationalist sentiment, the internet-fueled movement managed to gain international attention. The failed efforts of the Russian government to control the flow of information only hardened Siberian resolve. Protests grew into active resistance, leading to violent confrontations as the Russian government’s crackdown turned increasingly brutal. After the killing of the Siberian governor by separatists, the conflict escalated into an all-out insurgency. The assassination of local officials and the retaliation by Russian forces resulted in the first organized armed uprisings against Russian military units.

Chinese Involvement and the Escalation to War

The discovery of Chinese arms in the hands of Siberian rebels marked a turning point in the conflict. Moscow, already suspicious of China’s growing influence in Siberia through economic channels, now faced the possibility of a proxy war on its eastern front. The use of Chinese-made anti-tank missiles and weapons in Siberian ambushes against Russian convoys further inflamed tensions between the two powers. As Moscow deployed its 36th and 41st Armies to crush the insurgency, Siberian rebels, now bolstered by international support and covert Chinese aid, mounted a fierce defense, using guerrilla tactics to neutralize Russian armor and personnel.

The Kremlin’s heavy-handed response, including the deployment of the Russian military to suppress local unrest, triggered a backlash not only among the Siberian population but also in the international community. The destruction of internet communication networks was a temporary setback for the Siberian separatists, but the international media coverage of Russian atrocities further rallied global support for the Siberian cause. As the situation spiraled out of control, Moscow found itself increasingly isolated on the world stage, unable to garner sufficient support from the United Nations to label the Siberian National Party as a terrorist organization.

The Russian Retreat and Siberian Independence

The tipping point came when Siberian forces, emboldened by their success in the field and growing international recognition, began to openly challenge Russian sovereignty in the region. When NATO and other international actors began mediating between Moscow and the Siberian nationalists, the Kremlin was forced to negotiate, realizing that continued conflict would risk full-scale international intervention. Russia, battered by internal dissent and an increasingly fragile economy, reluctantly agreed to grant Siberia legal autonomy, which later led to full independence.

In the aftermath of these negotiations, Siberia declared itself the People’s Republic of Siberia, much to Moscow’s dismay. However, the real challenge for the new nation began when it inherited nearly 300 nuclear warheads and significant military hardware left behind by the retreating Russian forces. Unlike Ukraine and Kazakhstan, which returned their nuclear arsenals to Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, Siberia chose to keep its weapons as a deterrent against future aggression from both Russia and China. The existence of these nuclear stockpiles complicated international relations and made Siberia a critical player in global geopolitics.

Post-War Siberia and the Rise of a New Power

With its newfound independence, the Siberian Republic quickly began establishing ties with Western powers, especially the United States. The Siberian constitution, modeled closely on the U.S. Constitution, guaranteed citizens a wide range of civil liberties, including the right to bear arms—a symbolic rejection of Russian authoritarianism. The newly formed Siberian National Congress worked closely with international partners to develop Siberia’s natural resources, transforming the region into an economic powerhouse.

In particular, Siberia’s abundant oil, natural gas, and mineral reserves became a linchpin in its economic growth, attracting foreign investment and fueling its rise on the world stage. The Siberians, wary of Chinese expansionism, limited Chinese involvement in their economic projects while fostering close ties with the United States. Joint ventures with American companies in advanced technology sectors—ranging from robotics and biotechnology to renewable energy—positioned Siberia as a key ally for the U.S. in the region, further antagonizing the Kremlin.

Siberia’s Arctic ports, once frozen and inaccessible, were developed into vital trade routes, linking the region with North America and the rest of the world. The construction of joint U.S.-Siberian naval bases in the Arctic solidified the Siberians’ defensive posture against Russia and China, securing their geopolitical future as a crucial player in the post-Russian order.

The Long Shadow of Russia

Despite Siberia’s rapid rise as an independent state, tensions with Russia remained high. The Kremlin’s refusal to fully acknowledge Siberia’s independence, combined with its loss of strategic military assets, continued to strain relations. Periodic skirmishes between Russian loyalists and Siberian forces persisted, particularly in contested border regions. Moscow’s determination to reclaim Siberia’s resources and strategic value ensured that the threat of conflict would linger for years to come.

However, with the backing of international powers and a strong national identity forged in the crucible of war, Siberia stood firm. Over the next decade, the People’s Republic of Siberia became not only a regional power but a global player in the energy, technology, and military sectors, reshaping the geopolitical landscape of Eurasia. In this new world order, Siberia’s unique position between Russia, China, and the West ensured that its future would remain at the heart of international diplomacy and conflict resolution for generations to come.

Siberia’s Strategic Role in Global Politics

In the decades following its independence, the People’s Republic of Siberia evolved into a pivotal actor in international politics. Positioned between the Russian Federation to the west and China to the south, with direct access to the Arctic and the Pacific, Siberia controlled some of the most strategically valuable territory in the world. Its natural resources—vast reserves of oil, natural gas, minerals, and rare earth elements—made it a coveted partner for global powers, including the United States and the European Union, both of which were eager to reduce their dependence on unstable or unfriendly suppliers.

Siberia’s decision to retain its nuclear arsenal complicated its relationships with other nations. Although Siberia had no immediate ambitions to expand its influence through military conquest, the presence of nearly 300 nuclear warheads made it a formidable force. International efforts, led by the United Nations and supported by Russia, China, and the European Union, aimed to convince Siberia to disarm, or at least commit to non-proliferation agreements. Siberia, however, maintained that its nuclear stockpile was a necessary deterrent against any future aggression from either Moscow or Beijing, especially in light of Russia’s past interventions in Ukraine and Georgia.

This nuclear dilemma placed Siberia in a unique but precarious position. On the one hand, its possession of nuclear weapons guaranteed it would never be ignored on the world stage. On the other hand, the international community remained wary of an independent state with a relatively small population holding such a powerful arsenal, particularly when its two neighboring superpowers—Russia and China—were increasingly assertive in their geopolitical ambitions.

U.S.-Siberian Alliance and the New Cold Front

Siberia’s strategic alignment with the United States became one of the defining features of global geopolitics by the 2040s. Recognizing Siberia’s critical geographic location and its rich natural resources, the U.S. quickly moved to establish close economic and military ties with the new republic. American companies were granted access to Siberia’s natural resources in exchange for massive investments in infrastructure, technology, and defense. This included the development of Arctic ports and the expansion of Siberia’s railway networks, which became a key component in linking Siberia’s vast and sparsely populated regions with the rest of the world.

Siberia also became a focal point in the growing tensions between the U.S. and China. The construction of joint U.S.-Siberian Arctic naval bases, aimed at protecting the new Arctic shipping routes opened by global warming, further exacerbated tensions with both China and Russia. Siberia’s proximity to the Arctic and its control over critical northern ports allowed it to serve as a crucial partner in securing America’s interests in the region, including the exploitation of Arctic oil fields and the management of new shipping lanes between Europe, Asia, and North America.

This U.S.-Siberian partnership sparked what many began calling a “new cold front,” a geopolitical contest reminiscent of the Cold War but focused on the Arctic and Siberian resources. China, while supportive of Siberia’s independence early on, became increasingly wary of Siberia’s closeness with the U.S. Beijing viewed Siberia as an important counterbalance to Russian influence, but as Siberia began enforcing economic barriers to limit Chinese investment, tensions rose. China’s need for natural resources, particularly as its population grew and its industrial economy expanded, made Siberia’s vast untapped mineral wealth highly attractive. However, Siberia’s close ties with the U.S. and its restrictions on Chinese access to these resources created friction between the two nations.

Siberia’s Economic and Technological Ascendancy

By the 2050s, Siberia had fully established itself as a key player in the global economy, fueled by its booming energy exports and cutting-edge technological sector. Leveraging its vast raw materials and strategic alliances, Siberia positioned itself as a leader in several critical industries. Its joint ventures with American and European firms allowed it to capitalize on advances in renewable energy, robotics, biotechnology, and nanotechnology.

One of the cornerstones of Siberia’s economic success was its aggressive push into renewable energy. With abundant geothermal, wind, and solar potential, Siberia transitioned from being a petrostate reliant on oil and gas exports to a leader in green energy technologies. This not only helped it diversify its economy but also positioned it as a global player in the fight against climate change. Siberia’s renewable energy initiatives attracted significant investment from Western nations, eager to transition away from fossil fuels while ensuring access to reliable energy supplies.

In addition to energy, Siberia’s thriving technology sector emerged as a global leader in advanced robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and materials science. In partnership with U.S. tech firms, Siberia became a center for the development of next-generation AI systems, autonomous industrial machinery, and high-tech manufacturing. Its universities, many of which had been established in the Soviet era but modernized and expanded post-independence, attracted the best and brightest from around the world, turning Siberia into a hub for technological innovation and research.

The Rise of the Arctic Trade Routes and Siberian Global Influence

Perhaps the most significant development in Siberia’s post-independence trajectory was the rise of Arctic trade routes. As global warming melted the polar ice caps, new shipping lanes opened up, drastically shortening the distance between Europe, Asia, and North America. Siberia, with its extensive northern coastline and Arctic ports, became a critical player in managing these routes.

The development of Arctic infrastructure, including icebreaker fleets, deepwater ports, and rail networks connecting the Arctic to the heart of Siberia, turned the once-remote region into a major global trade hub. Siberia’s ports in the Arctic became key nodes in the global supply chain, reducing shipping times and costs for goods moving between Asia, Europe, and North America. This new economic lifeline brought tremendous wealth and geopolitical influence to Siberia, making it a vital partner in international trade.

The strategic importance of the Arctic routes also drew increasing attention from global powers. While Siberia remained a staunch ally of the United States, it carefully navigated its relationships with other major powers, including the European Union and India, both of which sought access to these critical shipping lanes. This balancing act allowed Siberia to expand its influence beyond its borders, shaping global trade and logistics in ways that echoed the power wielded by traditional maritime nations like the U.S. and China.

A New Geopolitical Order: Siberia as a Global Power

By the second half of the 21st century, Siberia had grown into a fully-fledged global power. Its ability to leverage its natural resources, strategic location, and technological advancements allowed it to play a pivotal role in shaping the global order. The People’s Republic of Siberia, once a breakaway state struggling for survival, became a beacon of democracy and innovation in a region traditionally dominated by authoritarian regimes.

Siberia’s strong ties to the West, particularly its close partnership with the U.S., ensured that it remained a key player in counterbalancing Russian and Chinese influence in Eurasia. However, its independence, economic success, and military strength also made it a target for regional destabilization efforts. Despite this, Siberia continued to assert its sovereignty, using its wealth, military might, and nuclear deterrent to secure its position on the world stage.

In this new geopolitical landscape, Siberia’s rise represented a major shift in the balance of power in Eurasia. It marked the emergence of a new world order, one in which smaller but strategically significant nations could influence global politics, technology, and economics, shaping the future of the planet for generations to come.